Arts and Crafts

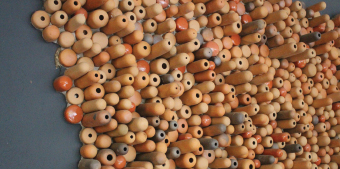

Dominican artisans have created a popular utilitarian and aesthetic art in which they display their unique cultural identity, and they do so creatively using everything they can get their hands on: cabuya, guano, mud, semiprecious stones, wood, shells and recyclable materials.

From province to province, Dominican crafts are diverse, creations are inspired by the resources that are available in the environment, and manual techniques are transmitted from generation to generation.

As a whole, these expressions of popular culture contain elements of the aboriginal, Spanish, and African ancestors.

As a whole, these expressions of popular culture contain elements of the aboriginal, Spanish, and African ancestors.

In the same way that the pieces linked to the ceremonial practices of the Taínos appear today as manifestations of the aboriginal art, those that were utilitarian articles of other generations have become artistic expressions of the popular creativity. Good examples are the peasant hats of Gurabo and the arganas used to transport products, distinctive baskets weaved with cane and guano from Cibao.

Natural Fibers

Vegetal fibers constitute one of the most traditional raw materials of the Creole crafts. Some of the most typical articles made of guano are the serons, the macutos or travel bags, and the saddles for the animals called “aparejos.”

The weaving of moorings, hammocks and strings of cabuya, in which the Taínos were skilled, is currently combined with synthetic fibers.

The higüeros of the pre-Columbian utilitarian crafts are today the base of artistic carvings, openwork and painting of figures, faces, packaging, diverse adornments and jewelery, in La Romana and in Santo Domingo. In addition, they are used to make traditional maracas painted and decorated in low relief.

While the coconut palm fibers are used to make curtains and lampshades in the town of Las Terrenas, province of Samaná, the jícara or peel of the fruit is the raw material for the butterflies that are made in the city of Moca. The latter were the winners of the 2006 UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts.

Did you know? “Vases, napkin rings, spoons, necklaces, bracelets, card holders, wallets, trays, cup holders and pencil holders” can also be created with jícara. Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican (https://www.amazon.com/All-Things-Dominican-Lo-Dominicano/dp/9945590243)

The skillful hands of the artisans of Canoa, in Barahona, weave baskets with plantain leaves, and turn the vine into original dolls.

The use of natural fibers has diversified with artists that unify the design with Dominican brand crafts, such as Dahianna Blanco, whose production highlights her series of mosaics decorated with guano sheets; Orlando Issac, with his collection of wood and guano chairs with minimalist lines; Roberto and Mencía Zagarella, father and daughter, who mix organic and geometric forms and craft traditions; and guano and cloth tents, by Patricia Castillo and Rafael Morillo.

Inspired by the urban landscapes of the community of El Limón de Mata de Jobo, young designer and artisan Paolung Lee, makes attractive lamps with materials extracted from the acacia bush, and guano weaves combined with synthetic threads.

Summer handbags, wallets, flowerpots, baskets, containers, adornments and furniture are part of a high-end manufacturing process, appreciated by interior designers that infuse vernacular accents to their decorative schemes.

Thus, the appreciation for the less traditional craftsmanship of a new generation that combines artisanal with modern design. Among them we find Jenny Polanco, Sissy Bermúdez, Roberto Zagarella, Rafael Morla, Cayuco, Odilia Almonte, Roxanna Antigua, Juan Puello, Cristina loriver Cordero, Simón Muñoz, Jorge Caridade Hilario Grullón, and others.

Molding the Clay

The artisanal pottery of the burenes has a native heritage. It is used to make cazabe jars and pots, a specialty of the towns Reparadero and El Higüerito, in Moca, Espaillat province.

Did you know? The famous faceless dolls of Limé are molded in clay, dressed in long, stylized dresses, wearing elegant hats or as sellers of water in jars, with brightly colored handkerchiefs covering their heads, according to the book “Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican” (https://www.amazon.com/All-Things-Dominican-Lo-Dominicano/dp/9945590243).

The dolls without facial features are an original creation of Dominican sculptor Liliana Mera. Her creation gave way to numerous variations in Moca, Bonao, Baní and San Cristóbal: sellers of coffee, fruit, jars and flowers, sweepers, representative of the tasks of women workers of anonymous faces.

As popular as the dolls are the works with Taíno motifs modeled by hand in the towns of Los Calabazos, Jarabacoa; in Guaigüí, La Vega, and in Yamasá, Monte Plata. Figures of cemíes, vases, containers, inspired by anthropological studies, like those of the Guillén brothers, whose ethnic art intends “to rescue the Dominican background in unique pieces.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.)

The Guilléns are five potter brothers settled in Yamasá, researchers of the native roots, who recreate the original Taíno pieces while teaching the craft to young people of the community.

Pottery is a large industry in Bonao, Monseñor Nouel province, which has white and red mud mines in the area, raw material for attractive jars of all sizes and types, as well as pots, containers and decorative rustic pots. The BONARTE company was one of the pioneers in the production of pieces that are “resistant and attractive ceramics made with greenish mud in high temperature.”

Unique in their class are the “Las Casitas de Chavón” clay creations, the work of Nelson García, a miniature incarnation of the sixteenth century Mediterranean villa created by industrialist Charles Bludhorn in 1973. The quality of the stylized ornaments is not left behind: vases and lamp bases with incisions, painted in acrylic, produced in the ceramics workshop of the Escuela de Diseño Altos de Chavón, in La Romana.

Artist Ana Iris de la Rosa, from San Pedro de Macorís, sculpts the figures of musicians, players, teachers, and workers, portraying the daily activities of the people.

Pieces of Wood

Wood carvings, large and small, decorative, religious and of daily use abound in Dominican crafts, and many are inspired by the indigenous and colonial past.

Artisans of the East, North and Northwest rescue indigenous art from oblivion, reproducing musical instruments such as the mayohuacán, a wooden drum that the Taínos used in sacred ceremonies; axes, caritas, duhos or cacique seats, and tutelary deities carved in guayacán, one of the tropical woods on which the Taínos carved conceptual and utilitarian pieces.

Anthropomorphic neo-Taíno figures recreate the remote past in the Guayacanes of San Pedro de Macorís, in La Isabela of Puerto Plata, and in Las Galeras of Samaná. Some are crouched in ceremonial position, with circular plates on their heads, evoking the sacred ceremonies of the cohoba, during which caciques and buhitíos inhaled hallucinogenic powders to come into contact with the invisible world.

Native motifs began to be used in crafts after anthropological research was promoted in the second half of the twentieth century by Emile Boyrie Moya, the pioneer of Dominican archeology.

The wood saints of popular religiosity, of Hispanic legacy, common in the fields since colonial times, have a group of cultists in Bonao, grouped into a collective, whose works have earned national and international awards.

Sacred images of Catholicism, with their diversity of virgins, nativity scenes, hearts of Jesus, saints and crucifixes, were awarded the 2006 UNESCO Award of Excellence for Handicrafts.

The wooden crafts with the Cayuco seal in Miches, represent the boats of this town and those of the bay of Samaná, as well as natural elements, fish and figures of fishermen.

Pylons are made of baitoa, in Boquerón, Azua, with white and resistant wood that iseasy to work and polish. In the community of El Pino, located between La Vega and Bonao, they produce batches of almacigo, valuable wood that is also used to make boxes.

Wood bird carvings are typical of the mountainous area of Cambita Garabitos, San Cristóbal, and they owe their origin to craftsman Erasmo Puello, who started making spoons for his wife and ended up selling them in the village. He later moved on to making pigeons, parrots, and continued with macaws and the famous UNESCO award-winning roosters of bright red, blue, and yellow colors.

Today, his son Juan Puello de Jesús, who has followed the tradition, travels through Asia, Latin America and Europe selling and exhibiting at craft fairs.

A craftsman who combines wood with metal and vinyl is Ricardo Nicasio who recreates in miniature the typical cars of his hometown, Santiago de los Caballeros. His passion for craftsmanship managed to transcend the prison bars and demonstrates that art can “support processes of regeneration and personal transformation.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.)

“Art is therapeutic, it is edifying and unites us as human beings, beyond the conditions we are in,” says Nicasio.

Artisans of the South and other areas have worked with equal ardor to further the carpentry of chairs, shelves, rocking chairs, tables, decorative and everyday use objects, worked in mahogany, oak, guayacán, acacia, nursery, bamboo, and pine.

Stone Carvings

Artisans of the city of Imbert, Puerto Plata, sculpt zoomorphic figures, baseballs, Taíno deities, images of Catholic saints, chess pieces, dolls, and other objects to which they give a petrified wood appearance. They sculpt on soft stones of brown veins that are found in that area.

The raw material is the sedimentary rock called arenisca (sandstone) and the talc, a white, blue and gray mineral of slight hardness, that the artisans excavate in the quarries of the area.

The Association of Artisans of Petrified Wood (Asoartep) brings together the first and possibly the only organization of carvers, which obtained a certificate of collective trademark of Imberlita that identifies their crafts, granted by the National Office of Industrial Property.

Stones extracted from rivers and corals are carved, equally, in Padre Las Casas, Azua, and in the Bancos de Guayacanes, in San Pedro de Macorís, where artisans Narciso Coca and Rafael Villegas create excellent reproductions of cemíes and figures from the Taíno mythology.

The natural skill in the art of carving exhibited by Dominican peasants became apparent at the end of the 50s, when villagers from La Caleta began to replicate archaeological pieces from Los Paredones cave, five kilometers north of the Santo Domingo-San Pedro de Macorís highways.

Peasant Ramón Mosquea (Benyí) led a group of men and women who made false pieces that they buried to give them the appearance of antiquities and that for many years were purchased as originals, although scholars had warned that the excavated figures had large dimensions and Negroid features. Beyond the fraud, it remains the fact that the locals created “a new art, a contribution to the Dominican handicraft that reveals the imagination of its creators,” as Archaeologist and Anthropologist Marcio Veloz Maggiolo pointed out in an article.

Jewelry

“In traditional Dominican jewelry the designs integrate resins and semiprecious stones, such as amber and larimar, which are embedded in precious metals such as gold, silver and platinum and, in rare cases, in bronze and copper.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.)

Dominican amber, according to the publication, is internationally recognized for its transparency, the diversity of specimen inclusions and treasures such as scorpions, lizards and frogs trapped in the resin.

The Amber Museum in Puerto Plata, where much of the valuable resin is concentrated, and a similar one in Santo Domingo, exhibit and sell fine jewelry, which can also be obtained in craft shops, hotels and shopping centers.

The beauty and uniqueness of larimar has been taken advantage of by the Dominican artisans who operate workshops in the capital, in Santiago and in Puerto Plata.

This “rare variety of pectolite or semiprecious rock is only found in the Dominican Republic.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.) Light blue, greenish-blue and deep blue, it was first detected in 1916 and rediscovered in 1974 on a beach in the southern city of Barahona, where Los Chupaderos larimar mine is located, the only one known in the world.

The amber and larimar jewels have become a “country-brand.” In 1950, artisans from Cooperativa de Industrias Artesanales (COINDARTE) produced elegant pieces of amber under the tutelage of artisan jeweler Emilio Pérez and Yugoslav artist Iván Gundrum, which were exhibited at the Fair of Peace and the Confraternity of the Free World, which was held in Santo Domingo in 1955.

Jewelry of seashells, dolomite mineral rock, coral, bones, beef horn and leather are less iconic, some of which recreate Taíno pictographs.

Crafts Using Recyclable Materials

Dominican artisans see unusual possibilities where many see waste. For example: belts, purses and hats are made using cans and bottles. Earrings, bracelets and bags are made with PVC tubes, paint cans and old acetate discs.

William Núñez creates dolls and puppets from plastic and cardboard, which he adorns with acrylic paint and suede.

Brotherhoods of religious musical tradition of Villa Mella, San Pedro and San Francisco de Macorís begin to manufacture their percussion instruments with plastic, PVC and X-ray films that produce new sounds.

Carnival masks made of cardboard, crepe paper or “papier-mâché” are another proof of the inventiveness used to enhance community identity, such as the masks of Milcea González, from El Seibo, who tell the stories and legends of their people.

Did you know? The ReCrearte program of the Global Foundation for Democracy and Development (GFDD) conducts creative recycling and environmental awareness workshops in the Dominican Republic. Learn more about this program by visiting its website: www.recrearte.org

Other materials

In addition to the traditional saddlers of the East of the country, experts in the manufacture of hats, belts, cases and other leather goods demanded by farmers and the sugar sector, there are artisans in Santo Domingo dedicated to creating leather accessories: necklaces, bracelets, belts and wallets for men and women.

A relatively recent material in Dominican crafts, which is growing over time, is bamboo. It was introduced in 1977 by a mission from Taiwan that worked with the Dominican government in the installation of a center to train craftsmen in the production of furniture and other articles made with this raw material.

Fabrics and threads, on the other hand, have been used since colonial times to make embroideries of tables, trays and bedspreads, rag dolls, carnival costumes and rugs for the mounts of pack animals, whose uses have evolved throughout the centuries.

Currently, these rugs are made in Bonao using old bags and pieces of cloth, with notable improvements in “the uses, sizes and designs.” “In addition to rugs, this technique produces cushions, bedding and decorative items for homes and cars.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.)

The same goes for the tobacco from the Cibao Valley, appreciated as one of the best in the world. Industrial and artisanal cigars are made using it and “many people today value them over the famous Cuban cigars.” (Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican.)

Cultural Heritage

The Taínos were skillful artisans of utilitarian and ceremonial articles made of wood, clay, stone, shell, cotton, henequen, maguey, cabuya and vines. They elaborated figures of their deities, vessels, pots, plates, amulets, stamps, hammocks, fishing nets, threads, ropes, cloths, skirts and baskets with these materials, in addition to musical instruments, such as mayohuacán, rattles and maracas.

On the Spanish side, the legacy began with the pottery artisans who came to the colony to make the daily items that were necessary for them: jars or containers for storing olive oil, olives, almonds, honey, and inedible products, such as gunpowder and mercury.

They introduced jewelry techniques and ceramic decoration on porcelain with spandrel lead enamel and decorated with oxides, which has been known since the Renaissance as majolica of Arabic origin.

Musical instruments from the African tradition are the tambora (drums) and atabales (sticks), specifically the ritual drum of the zarandunga dance, tambora de la salve, merengue, bongo and conguito, many made in Villa Mella, Santo Domingo, according to data contained in the Catalog of Dominican Crafts, published by the Ministries of Industry and Commerce and Culture.

Also, the drum of the greater congo and of the minor congo, and the drum of the gagá, of Barahona, and the pandora de salve made in Santo Domingo.

Sources and Other References

- Lo Dominicano / All Things Dominican, a publication of Global Foundation for Democracy and Development (GFDD), 2016. Available through Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/All-Things-Dominican-Lo-Dominicano/dp/9945590243

- Arquitexto.com/diseñania y guaneando/exposiciones.

- Artesanosauténticos.com

- Eldiariony.com

- Rossydiaz.wordpress.com

- Periódicoelfaro.com.do/artesanía Imbert.

- Rifta.net/libro Casos de organizaciones artesanales competitivas de América Latina/Autonomous University of Querétaro, 2013.

- Elogio y sentido de Los Paredones, artículo de Marcio Veloz Maggiolo, Listindiario.com/2014/06/20.

- Paredones: arte colombino o falsificaciones contemporáneas? Bernardo Vega (hoy.com/junio 14, 2014).

- Catálogo de la Artesanía Dominicana, Ministries of Industry and Commerce and Culture.

- Artesanía Dominicana: un arte popular, M.A. de la Cruz y Víctor Manuel Durán Núñez.