Music

Dominicans live in such contact with music and dance that, without effort and without undergoing any kind of learning, they have become musical beings. Either sitting or standing, they carry the beat of a song with their feet, and unconsciously move their bodies, keeping the tempo.

It is not surprising that, as a people, Dominicans have produced countless musical expressions, some of which are world-renowned, and others that scholars studying Dominican folk music have found to be known only in specific communities in the country. Moreover, some expressions are linked to religious festivities and are disseminated during special presentations by folk groups.

In general, this music has simple rhythms which are often repetitive. They appear to mimic heartbeats, and seem to have an automatic, enthusiastic and resonating effect that permeates the spirit and makes the body vibrate.

Like all manifestations of folk culture, some of the uniqueness that characterizes these melodies and even their origins — about which academics tirelessly argue — always appears to be enveloped in a certain historical fog.

Like all manifestations of folk culture, some of the uniqueness that characterizes these melodies and even their origins — about which academics tirelessly argue — always appears to be enveloped in a certain historical fog.

What happens is that nobody announces their appearance, because a musical genre of this type never appears fully articulated. Instead, it presents itself as a kind of rhythmic element that changes due to constant fusions and influences of other trending rhythms, in an identifiable but endless chain of metamorphosis.

The Dominican people evolved from a mixture of cultures, essentially the European of the conquerors and the dominant powers in the country’s formative stage, and later the African of the slaves. The cultural manifestations that make up Dominican traditions — popular music among them — represent the combination of those same extracts.

This same phenomenon takes place throughout the history of uniquely Dominican musical expressions which have become universal; expressions in which rhythmic combinations or interpretations with a variety of instruments are a given.

These emerged as popular creations in an eminently agrarian society. Musicians used them as vehicles to tell stories, or to express what delighted or saddened them, and what they disliked or what pleased them. And their poetry responded to those states of mind, which were expressed in a raw and unadorned manner that characterized the socio-cultural level of its authors.

This type of music’s appearance in urban party lounges resulted from a long evolutionary process of creating legitimacy and counted on the support and contributions of musicians and arrangers in incorporating new instruments to their performance. Above all, these actors elevated the level of their poetry to make it more “acceptable” to a more sophisticated environment.

We invite you to learn more about Dominican music and rhythms through the ALL THINGS DOMINICAN | Lo Dominicano publication, which is available on Amazon here.

Did you know? Sol Caribe, a documentary, was produced in 2010. It discusses the main features of Dominican folk music, from the point of view of its musicians. Watch the trailer here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=08A8jHPTons

Popular Dominican rhythms: Folk music

Among popular Dominican rhythms, merengue and bachata are the two best known genres, due to the widespread dissemination they have achieved. This is a result of two important phenomena: massive migration and the rise of successful performers and musical groups. Having to compete with musical manifestations that dip in and out of fashion, both have been the focus of instrumental and harmonic modifications. Their adaptation, clearly, has ensured their permanence.

Many other rhythms, which have not had such creative enthusiasts, have not gained international fame, though their expressions remain alive and faithful to their original features. This is a result of interpretations from many existing folk groups; an example of the musical richness of Dominican popular culture.

There are other less known rhythms, linked to the practices or rites of popular religions: cultural manifestations that have remained unchanged over time, and which are practiced by small groups in some villages. These are considered equally defining elements of the Dominican identity.

Merengue

Do not miss this wonderful video: ¡Qué Viva el Merengue!

No researcher has been able to find merengue’s “birth certificate,” but those who have traced the history of its evolution as a folk rhythm and dance agree in recognizing that it is the musical symbol of the Dominican people’s own identity.

No researcher has been able to find merengue’s “birth certificate,” but those who have traced the history of its evolution as a folk rhythm and dance agree in recognizing that it is the musical symbol of the Dominican people’s own identity.

Journalist Luis Eduardo Lora (Huchi) confers to merengue a “decisive influence” on Dominicans’ cheerful temperament.

The people use merengue’s poetry to talk about social or political reality, or to discuss historical or daily events in their lives. Yaqui Núñez, a well-known Dominican TV presenter, said it well: “From the beginning… from the first inhabitants… music has been a means not only to tell, but to sing the history of this country. Here, at the door to the New World, there has always been a singing dancing and a dancing singing.”

Did you know? On November 30, 2016, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared Dominican merengue as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The Intergovernmental Committee, at its annual meeting in Addis Ababa, made this decision, considering that Dominican merengue “plays an active role in a diversity of areas in people’s daily life: education, social and friendly gatherings, festive events, as well as political campaigns.” UNESCO highlighted that this element of intangible cultural heritage “is transmitted, primarily, through participation, and its practice attracts people from very different social strata,” thus contributing to “fostering respect and coexistence among communities.”

Merengue is the most universal Dominican popular music. It began to be noticed as a distinctive form in the mid-19th century, welcomed by an impulsive youth that broke with the solemn molds of the trending European rhythms of that time, above all in the Cibao region, located in the center of the country. Twenty-five years later it started to be welcomed in some clubs in urban areas.

Merengue has experienced the most changes of any musical expression. Because of this, researchers studying its rhythmic distinctiveness have identified numerous varieties in its interpretation, from the instruments that are used to its tempo.

In the beginning, it was played with a set of guitars, the güira, the tambora and the marimba. However, in the last third of the 19th century, the diatonic accordion, of Germanic origin, replaced the guitars.

Subsequently, the marimba, which imitated the sound of a double bass, was replaced by an electric bass guitar. Then the saxophone was incorporated, and some music bands used the piano. The güira, made of metal, is an authentic Dominican instrument. It is a scraper, which bears some resemblance to the traditional güiros made of dried gourds. It is played by holding it vertically, one hand grasping its handle and the other scratching the grooves in its surface with a hook that ends in the form of a comb with metallic prongs.

Merengue is made of three parts or sections. It begins with the so-called “paseo (stroll)”, an instrumental introduction that sounds like a kind of slow march. It is followed by the “body of the merengue,” which is the singing and dancing section. And it concludes with the “jaleo,” which is characterized by vocal refrains. After the “jaleo,” the singers repeat the chorus.

The rhythm that characterizes merengue is made by the tambora, whose sound comes from the use of both hands. It is a two-headed drum, cylindrical in shape and made of a hollowed-out tree trunk. Its uniqueness comes from having the leather of a male goat on one side, and the hide of a female goat on the opposite side, both tied with cabuya ropes. The leather on the right side is played with a drumstick, and the leather on the left with the palm of the hand.

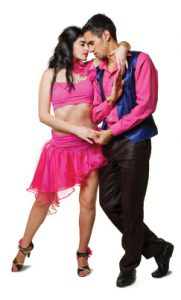

Merengue is danced in pairs, which move their legs and hips while they remain locked in embrace, and move around the room, sometimes taking steps and making shapes that mimic the movements of other rhythms that have influenced the changes experienced by the merengue, such as jazz, the twist, and rock and roll.

Some researchers identify four variants of Merengue: 1. Merengue Liniero, originated in the so-called Northwest Line; 2. Merengue Quebrado (Broken Merengue); 3. Merengue de Pregunta y Respuesta (Question and Answer Merengue); and 4. Merengue Pambiche.

Folk researcher Fradique Lizardo establishes a list of eight variants: 1. Merengue Cibaeño, the so-called “emblematic” or “perico ripiao”; 2. Merengue Liniero; 3. Merengue Juangomero, from the North-eastern town of Juan Gómez; 4. Merengue Pambiche; 5. Merengue Redondo, which is exclusive to the province of Samaná; 6. Merengue de Atabales, from the Southeastern region; 7. Merengue Ocoeño, from the Southern city of San José de Ocoa; and 8. Merengue de Balsié, which is played in the Southwestern region.

Two other recent variants are Merengue Maco, or “a lo Maco,” whose distinctive characteristic is a rhythmic change on how the tambora is played; and, the Merengue de Calle, which introduces the timbal as part of the orchestra and presents an increased tempo.

“Merengue is always happy; I believe that it has influenced the cheerful temperament of Dominicans in a decisive way.” Huchi Lora, Dominican journalist, in the Sol Caribe documentary.

Did you know? Luis Alberti has the unquestionable merit of being the principal Dominican composer to launch Dominican merengue to the international stage. ‘Compadre Pedro Juan’ is one of his most famous creations.

Bachata

Bachata is a more recent musical genre that emerged in the 1960s in the rural area of the Cibao region. It developed with clear influences of the old Latin American romantic music played by trios and quartets with guitars, accompanied by maracas, bongos, the güira, and claves, especially of the so-called Cuban rhythmic bolero.

“Bachata,” for Dominicans, means party; a festive social gathering, and this is the reason why the music played during those occasions ended up taking the name that was given to the parties. It was performed by music groups playing guitars, maracas and the marimba.

“Bachata,” for Dominicans, means party; a festive social gathering, and this is the reason why the music played during those occasions ended up taking the name that was given to the parties. It was performed by music groups playing guitars, maracas and the marimba.

Its early enthusiasts played the romantic verses of its songs with a tearful voice full of emotion. This, together with common themes — love, heartbreak, suffering, and disappointment — led to its characterization as the “music of bitterness.”

Its unique development, essentially urban, included a mixture with the Cuban Son and guaracha, which accelerated its pace of development. In addition, its poetry changed from romantic themes to social issues. With this transformation, Bachata became dancing music, gaining greater acceptance and dissemination.

In modern times, the electric guitar and bass, bongos, and saxophones have been introduced in its performance.

Bachata is played in a four-by-four beat. It is danced in pairs, and starts with a series of simple steps that produce a movement from front to back or from side to side. The first three steps correspond to the first three musical beats, and they are followed by a touch of the foot during the fourth beat. The woman begins the steps with her right foot, and the man with his left. Sometimes the couples dance tightly together, and other times, they make shapes with twists and turns and with movements of the hips.

Did you know? Juan Luis Guerra made bachata popular in the Dominican Republic during the 1990s and gave it a new style, similar to the bolero. In 2002, the song “Obsesión,” interpreted by the bachata group Aventura, marked the beginning of a new way of singing this tropical genre, mixing it with pop music and other genres.

The Tumba

It is surprising to know that, although virtually unknown today, until the middle of the 19th century, the contra dance known as La Tumba was considered the national Dominican dance. Little by little it was replaced by Merengue, whose reign of more than a century and a half lasts until present day.

A description of the dance, which appeared in the publication “Une visite chez Soulouque,” by French citizen Paul Dhormoys, who visited the Dominican Republic at that time, is as follows:

- Dancers form lines of two dancers per row; the men place themselves on one side, and the women on the other side. From the moment that the orchestra gives the signal, they make a quarter turn and face each other. At certain times, which are indicated by variations given with the clarinet, the partners dance together or face each other while posing and swaying. Once the first figure is finished, each young woman leaves her male partner to dance with the one closest to her. When every woman has danced successively with all the men present, La Tumba ends.

Researchers of Dominican popular music agree in pointing out that it was a local dance that derived directly from contra dance, in which several pairs dancing at the same time produce a variety of shapes. Its name indicates that couples dance facing each other.

One researcher, Edna Garrido de Boggs, describes it as a group dance, in which the couples form two rows facing each other. Shapes are formed and the couples exchange partners. Music, according to Boggs, is interpreted with the accordion, the guiro, and tambora.

Another researcher, Fradique Lizardo, points out that its choreography clearly originated in the courts. “So many bows and exchanges, and the attitudes of contempt, remind us of the attitudes during tournaments, jousting, mock spears, games of forfeiture and the like.”

Mangulina

For leading folk researcher Esteban Peña Morell, Mangulina is a local creation derived from the aguinaldos and jaleos of the Canary Islands. He says that this music is indigenous to the Dominican Republic and that it originated in Hicayagua, in El Seibo, from where it spread its popularity to the entire Dominican Republic. There are however those who dispute that it originates in the Southern region.

Several authors cite the existence of a traditional couplet in which the name of this style of music is derived from the name of a woman: Mangulina was called / The woman I had / And if I she had not died / Mangulina still.

Mangulina is a type of composition that consists of two parts: The couplet, with lyrics that may be either religious, political, erotic, or satirical, and the mangulina – the refrain.

Mangulina is a type of composition that consists of two parts: The couplet, with lyrics that may be either religious, political, erotic, or satirical, and the mangulina – the refrain.

The holding pairs dance fast, spinning first in one direction and then in another, combining the spinning with forward and backward steps. The musical groups that play it consist of players of balsié, accordion or violin, güira, and tambourine.

The Carabiné

In his study on the origin and distinctive features of this dance, folklorist Fradique Lizardo determines that the choreography of the Carabiné comes from another dance, the Isa: a song and dance indigenous to the Canary Islands. He says that it cannot be a coincidence that both have eleven equal shapes.

The Carabiné is a group dance, in which no less than six couples participate. Its tempo is two by four, and it consists of two parts: the stroll and the refrain. It is played with the accordion, the balsié, the güiro, the three, the four, the guitar, and the tambourine, and in some places violins with strings made of tripe are added. Usually, when string instruments are included, the accordion is not used, and vice versa.

The Carabiné is a group dance, in which no less than six couples participate. Its tempo is two by four, and it consists of two parts: the stroll and the refrain. It is played with the accordion, the balsié, the güiro, the three, the four, the guitar, and the tambourine, and in some places violins with strings made of tripe are added. Usually, when string instruments are included, the accordion is not used, and vice versa.

In the “paseo (stroll)” section, the couples enter the dance hall. The gentleman, with his right hand holds the left hand of his partner. In turn, she has her right hand on her waist. All the pairs form a circle with the men in the middle.

At the sound of the contramarcha, they turn in the opposite direction, leaving the ladies on the left side of their partners. The couples then separate while the partners dance facing each other. Steps to one side are followed by steps to the other side, like a rocking motion, while turning in place.

After that, they form a chain. The men grab the left forearm of their partner, with theirs passing behind her; then, they offer their right forearm to the next lady while she passes in front, and so on, until they reach their initial partner, with whom they end up dancing tightly holding each other.

The movements of the Isa Canaria are: a) the stroll of the man and the woman holding hands; b) chains; c) change of partners; d) rolls or rounds; e) the women inside the circle and the men outside, and vice versa; f) exit, holding hands like at the beginning.

One thesis about the dance’s name comes from the fact that the Haitian soldiers – “carabineers” who laid siege to the city of Santo Domingo watched the Dominicans dance it, and ended up emulating them, but keeping their guns on their shoulders.

Yuca

Yuca is a circular group dance designed to mimic the task of grating the cassava to make casabe, a Dominican tradition of Taíno origin. Several shapes are introduced in this dance, the most common of which is the number eight. From a musical standpoint, Yuca is a four-beat jaleo played with the güiro and the tambora. The tambora is played without sticks, using the fingers and the palms of the hands on the upper edge and at the patch.

Ramón Emilio Jiménez describes it as a “dance of shapes in which the couples form a chain through a successive and rhythmic series of exchanges. The linked couples greet each other and, at the sound of ¡yucca (cassava)!, they break their suggestive swaying, the mixed human chain in which the lady avoids other ladies and offers the lilies in her hand to various male partners.”

Ramón Emilio Jiménez describes it as a “dance of shapes in which the couples form a chain through a successive and rhythmic series of exchanges. The linked couples greet each other and, at the sound of ¡yucca (cassava)!, they break their suggestive swaying, the mixed human chain in which the lady avoids other ladies and offers the lilies in her hand to various male partners.”

We are told that “the dance owes its name of yuca to the isochronous noise (which is made of a continuous rhythm with periods of equal duration) of the white indigenous bread that comes and goes on the guayo, mimicked by the friction of the foot against the ground, which people call escobillar. When ¡yucca! is yelled again, the dancing chain is broken without anyone missing the beat for a single moment, and so the dance goes on amid the human chain that breaks and reforms again, until it dies with the cheers of the audience resonating.”

Chenche Matriculado

This is a very fast-paced dance, which is danced in pairs. It was very popular at the beginning of the 19th century.

The woman does a manner of ground stomping with her feet and moves them in long steps, combined with small rhythmic jumps. The man dances in a way that is called “espantada (frightened),” because he jumps and makes certain movements as if he were scared or in fear.

It is played, like so many other popular Dominican rhythms, with the accordion, the güiro, the tambora, and the saxophone.

Dance of the Clubs or Atabales

This is a musical genre related to popular religious rituals, with clear African roots, particularly from the Congo region, as has been determined by researchers of Dominican musical folklore. Moreover, they also argue that groups practicing this dance exist throughout the country.

J.M. Coopersmith, an American researcher of Dominican folklore, came to the conclusion that the Clubs or Atabales “is not really a dance, but rather a ceremonial form of singing in which secular or religious texts are used, or a combination of both, whether in the form of a ten-line stanza or a couplet of four verses.”

The solo and the answer is the technique of playing religious or festive Atabales, and it consists of a soloist singing the verses and refrain singers who answer him.

The instrumental group is made of three cylindrical drums of different dimensions: the main club – the largest one; the middle club, and the Alcahuete, the smallest one, and can include a güiro and small sticks to play on any surface that resonates. The main dancer is the lead singer, who, additionally, plays the main club.

For Coopersmith, what is most characteristic of the Atabales are the interruptions by the leader, at certain times, with a spoken text, during which the background music and replies by the refrain singers continue. When the ten-line stanza formula is used, a quatrain suggests the idea of a unification of the poetic structure; in the case of the couplet, the unifying element, in addition to the spoken outburst, is the repetition of each third couplet, changing the first two in each section.

Depending on the purpose, Atabales are classified in magical-religious clubs and ceremonial clubs. In the first, Catholic saints are worshiped, and in the latter, rituals are held to remember the dead or to make pledges. Festive Clubs are danced and sung. Clubs to remember the dead are played slowly, by rubbing the fingers on the leather of the kettledrum to simulate a moan. These are the so-called wakes or mortuary vigils.

In dancing Clubs people either dance in pairs or by themselves: the man chases the woman, indicating his role of conqueror and, in other cases, it is the woman who takes the initiative and guides the movements.

Sarandunga

The Sarandunga is a religious and festive ritual that emerged from a legendary story in which a statue of Saint John the Baptist, a Catholic saint, came into the possession of a family in Bani, who has kept it as a tradition for generations.

It is said that this statue, which is about two feet high, was acquired in Haiti, but there is no information about the origin of the rites that are carried out around it, or about the very name of Sarandunga with which its followers name the dance that initiate the celebrations.

The ritual is performed on June 24 of each year, or the day of St. John the Baptist in the Catholic Liturgical Calendar.

The ritual is performed on June 24 of each year, or the day of St. John the Baptist in the Catholic Liturgical Calendar.

On the morning of the day of the celebration, a Brotherhood or Fellowship formed by the family who owns the statue, its relatives, followers, and friends, brings the statue to bathe in the river. Then, all participants take a bath. Later, the statue, which is dressed in new garments every year, is placed on a platform, and then carried in procession to the family’s residence, where it is placed on a table.

At that moment, celebrations and festivals in its honor begin.

Popular games are played in the afternoon, and in the evening, celebrants dance the Sarandunga and sing “moranos,” which are refrains formed by a four-line verse of six syllables and aconsonantados (words rhyming in consonants), unique to traditional Castilian poetry. A variant of the Sarandunga is the “jacana,” which is a slower form of the dance.

The musicians use the güiro and three small tamboras, covered with leather only on one of their sides. They play and sing while seated with their instruments placed between their legs, and the audience sings along.

Once the music starts, a couple enters the ring and dances.

Folklorist Edna Garrido de Boggs describes the dance as follows: “The woman, with her skirt gracefully caught on both sides, touches her partner’s shoulder and takes the first steps, turning, depending on the case, from side to side, and always dancing in a circle inside the circle formed by the musicians and the audience, and without raising her eyes from the ground while dancing. The man, with a haughty posture and with a handkerchief in his right hand, shakes it before his partner and, depending on the case, chases her. Sometimes, the man raises his arms as if to embrace his companion, but she makes an opportune getaway, and the embrace does not take place. At other times, he stomps on the ground or they touch their shoulders, or the woman dances in front of him but, whenever he gets too close, she avoids contact. Except for the feet, no other part of the body moves.”

When a couple has danced enough, another couple enters the circle, and everything begins again.

Bandas

In the past, and still today, municipal and military bands have brought joy to the people with their open-air concerts and reveilles to commemorate every historical celebration. Some of these bands date back more than a century, replacing their members generation after generation. Each of these bands includes its own academy for training new members, to whom they must provide the required instruments. These municipal academies have always represented the greatest source of training for new performers and the continued operations of orchestras and other groups. However, demand for young and well-trained musicians by the music groups that operate in the most densely populated cities has, in the past, represented a serious problem for the maintenance and stability of municipal bands, and much more at present due to the boom and the popularity of these orchestras, a fact that explains the substantial increase in their earnings. The musicians of the municipal bands, in contrast, receive very precarious salaries, giving rise to the aforementioned exodus.

On the other hand, military bands attached to the various military bodies attract a good number of performers in search of more attractive salaries as integrated musicians. In addition to these salaries, they are drawn to the stability and permanence in these jobs, with little risk of suspensions.

Romantic music and songs

The bolero makes up part of the abundant treasure of romantic compositions of the Dominican Republic. It is to be noted that long before the appearance of this style as a genre, and specifically since the middle of the 19th century, this type of Dominican composition, with tightly woven melodies and lyrics with a refined poetic sense, is highlighted in documents of the era. Composers, whose names have been lost to history, wrote a collection of songs called the “Romanzas” (Romances). We have these beautiful pages of lyricism thanks to their careful collection by Professor José Dolores Cerón. They were also recently researched and connected with their authors by the academic and musicologist Miguel Holguin Veras in a praiseworthy effort.

Later, beginning in the thirties, new popular compositions categorized as boleros appeared in the Dominican Republic written by esteemed authors. Three of them have reached the highest pinnacle of respect in the Dominican musical realm for their permanence over time: Juan Lockward, Salvador Sturla and Manuel Sánchez Acosta. Throughout the following decade and supported by the Voz Dominicana, the national radio station, the country was introduced to a flood of prolific composers of songs and boleros whose cultural richness remains untouched by the effects of time and generations, as well as recent and successive trends, no matter how deep their cultural penetration appears to be.

From then on, the production of ballads and romantic boleros has remained constant, in number as well as in quality. One must understand, however, the challenge that music faces in a general sense, with a world in crisis, full of transformational events, one after the other. The musician-composer works under the inescapable influence of technological currents, fascinating and at the same time disturbing, that impose consumer desires at odds with creative thought. This conflict is even more notable in the realm of popular music, with all the weight of the market that restricts and manipulates it.

Santo Domingo has offered its answer to the challenges and objections of the restless society of today, joining lyrics of intense love, suffering, and abandonment with the simple melodies of yesterday, without pretentious or complex harmonies. The genre called bachata has brought about the best and unanticipated impressions in other latitudes, even in the furthest ones, though always under the protection of the communities of Dominicans abroad, who stand together with their hearts still fixed firmly in the country.

Bachata sings and weeps, though more the latter than the former, because in sadness lies its best weapon of penetration. It is, in effect, a cultural expression that, before being disdained by academics and music purists, should be pondered by all. And it should be contemplated even more by those who study social movements and social responses of people when their individual and collective interests are challenged by the harsh difficulties of life.

Traditional Dominican Instruments

The Güira, tambora and accordion are the musical instruments that define the so-called “perico ripiao” or “traditional ensemble.”

There are conflicting opinions on the origin of the güira. For some researchers, it was used by the natives under the name of guajey. Others maintain that it is of Dominican or Puerto Rican origin.

Initially, a güira made of pumpkin or squash was used, but at present, ones made of metal are preferred. These are commonly known as guayos.

The tambora (Dominican drum), a key instrument in the rhythmic structure of the national dance, comes from Africa. A local variant was especially built on the Northwest Line where they used a hollowed-out tree trunk with mounted patches on rings tied with a cord of pita fiber. Above these patches they placed leather made of a male goat’s hide on one side and that of a female goat on the other, which is the part that is played by drumsticks.

This sexual bipolarity becomes apparent in the rhythmic tempo of the merengue: While the palm of one hand hits its respective patch that serves as a damper, the other hand plays the percussion with a thin piece of wood. A third dry sound is made by the impact of the drumstick on the rim of the drum.

As in other manifestations of Dominican culture, popular music has been enriched with the importation of foreign musical instruments. Such is the case with the accordion, which arrives in the country in the late 19th century. The instrument arrived directly to the Cibao fields, a region that maintained an attractive commercial exchange with Europe, but especially with Germany.

Among the goods imported from Europe, the Austrian accordion arrived in the Cibao fields when the merengue was already in vogue, which until then based its music on Spanish string instruments: the guitar, the three, the four, and the triple.

Initially, these string instruments could hardly be heard due to the sound of the tambora and the güira. Hence, the accordion became the solution, moving quickly to replace the former and to form a trio with the latter. Subsequently, the trio expanded with the “marimba”, a rudimentary substitute of the double bass, and later with the saxophone.

Bibliography

- Music and Musicians of the Dominican Republic, J. M. Coopersmith.

- Dominican Music and Dominican Identity, Paul Austerlitz.

- El Merengue: Música y Baile de la República Dominicana, Catana Pérez de Cuello y Rafael Solano.

- All Things Dominican/ Lo Dominicano. GFDD 2015.

- Perlas de la Pluma de los Garrido, Edna Garrido de Boggs.

- El Carabiné: Origen y Evolución, Fradique Lizardo.

- Sobre Mangulina y Carabiné, Julio César Paulino.

- Pedro Henríquez Ureña. Historia Cultural, Historiografía y Crítica Literaria, Odalís G. Pérez.

- Juan Luis Guerra and the Merengue: Towards a New Dominican National Identity, Ramón Torres Santos.

- Kingston of Bachata, Laura Pierson.

- Instrumentos Musicales del Merengue Dominicano, Argenis Santana.

- Instrumentos Musicales del Merengue y su Evolución (www.8tiempos.com).

- Rafael Solano

- Sistema Nacional de Cultura de la República Dominicana