Dominican History

First settlers of the island of Santo Domingo

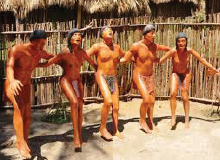

The first settlers of the island of Santo Domingo belonged to native people groups from the Orinoco river basin in Venezuela, as well as the Xingú and Tapajos basins in the Guyanas. They established themselves over four large waves of migration:

First migration wave: siboneyes, peoples with a shell culture that lived on the shores of rivers, swamps, inlets and bays. They did not have pottery or agriculture. They occupied some parts of the island.

First migration wave: siboneyes, peoples with a shell culture that lived on the shores of rivers, swamps, inlets and bays. They did not have pottery or agriculture. They occupied some parts of the island. - Second migration wave: known as Igneris on an archaeological level, they were of Arawak origin. They developed pottery.

- Third migration wave: product of the great Arawak expansion. Starting with this third population group, a cultural development independent of continental aboriginal traditions begins to develop, forming the Taino culture.

- Fourth migration wave: Caribs, also from the Arawak family, but with particular characteristics. They were great navigators, experienced in the use of the bow and arrow, and cannibals. They constantly made incursions into the eastern part of the island, besieging the Taino settlers. They mixed with the Tainos, forming the Ciguayo culture, located in the regions today known as Samaná, Río San Juan, Cabrera and Nagua.

Around the end of the 15th century, the Tainos ruled almost the entire island.

Diet

The Tainos were farmers, but also lived on hunting and fishing. They cultivated cassava, corn, sweet potato, lerén, peanuts, chilies, yautía, pineapple and tobacco. The people valued the meat of rodents such as jutías, quemíes and mohíes, in addition to hunting iguanas, snakes, parrots, seagulls and ducks. By fishing in the sea and the river, they fed on mullet, eel, sea bream, goldfish, rock cod, dajao, shrimp, crab, lambí and manatee, among others. They also enjoyed eating worms, snails, bats, spiders and other insects.

They made a type of bread from cassava called cazabí (today known as casabe). Its extensive use among the Spanish conquistadors, due to lack of wheat flour, gave it the name “bread of the Indies”.

Housing and Pottery

There were two different types of dwellings, or “bohíos”: the caney, with a circular base and conical roof, held up on the interior by a central post surrounded by other posts; and the type used by chiefs, of a wider, rectangle shape, with a two-side pointed roof and sometimes featuring a covered porch for visitors. Both buildings were constructed with the same materials: yagua and bejuco (vines).

The Tainos created various vessels and utensils for their daily tasks, such as pots, water jars, basins, spoons and cups, with mud and higüero (a type of wood) products. For sailing, they built canoes using a single trunk, generally of mahogany or ceiba. They slept in hammocks.

Social Stratification

- Naborías. These people were considered below the common population. They were servants that worked to maintain the wealth of the governing or “principal” classes (caciques, nitaínos and behíques). It is thought that they were the descendants of the Igneris conquered by the people that became part of the Taino culture.

- Common people. Their goods were considered collective.

- Behíques. Part of the upper class, they were priests that acted as intermediaries between men and the gods; also healers.

- Nitaínos. Part of the upper class; assisted the caciques.

- Caciques. Political chiefs, each had under his command a determined jurisdiction or territory.

Political Division

At the time of the discovery, the Tainos of the island of Santo Domingo were organized into five large confederations or chiefdoms, each under the rule of a cacique (chief):

| Chiefdom | Cacique |

| Marién | Guacanagarix |

| Maguá | Guarionex |

| Maguana | Caonabo |

| Higüey | Cayacoa |

| Jaragua o Xaraguá | Bohechío |

Family and Succession

Common people were monogamous. On the other hand, polygamy reigned among the caciques and nitaínos. The children (on average, three to five) were educated by their parents and the elders of the clan. The family clan was exogamous. The succession line went from fathers to eldest child, and lacking one of these, the line passed to the eldest son or daughter of the sister of the deceased.

Religion, Myths and Rituals

Their beliefs, myths and history were passed down orally through danced songs called areítos, in which a person recited the stories, and a chorus, composed of women, men or both, repeated them more loudly.

One of their myths narrated how the sun and the moon emerged from a cave named Jovovava; while another told of how the sea was created upon breaking a squash.

They performed religious rituals to cure the sick. Before proceeding with the treatment, the behíques inhaled tobacco and cohoba, an herb, to vomit and purify themselves, and to put themselves in contact with the cemí or god that would then tell them what to do.

Background to the Arrival of Columbus

Two trade routes

Trade between Europe and the Orient throughout the Middle Ages could be accomplished by two routes: the Silk Road, by which merchandise was transported in land caravans from China to the Black Sea and embarked from Constantinople; and a second one which had two different trajectories: one with stops in Baghdad and Damascus, ending in Palestine; the other used the Red Sea as a direct access to Alexandria.

The Columbus Proposal

Upon taking Constantinople in 1453, the Turks greatly affected European-Oriental trade. New routes to the Orient began to be explored. Christopher Columbus proposed, in various European courts, arriving to the East by sailing to the West. His idea was founded on the belief that the Earth was round, formulated by the Greeks, but until then, never proven. Basing his argument above all on the texts Tractatus de Imago Mundi by Pierre d’Ailly, Historia Rerum ubique Gestarum by Eneas Silvio Piccomini, Los Viajes de Marco Polo and probably the reports of Florentine mathematician and doctor Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, who had written on the possibility of arriving to the Indies from the west, Columbus calculated that the circumference of the earth was 30,000 kilometers (10,070 kilometers less than the actual figure). By his calculations, between the Canary islands and Cipango (Japan), there should have been 2,400 to 2,500 nautical miles, when in reality, the distance is four times greater.

Approval of the Proposal

After many years of traveling between European courts, Christopher Columbus found the sponsor of his enterprise. The Catholic Kings of Spain decided to support him, undoubtedly thanks to the favorable intercession of Antonio de Marchena (prior of the La Rábida monastery), Luis de Santángel (administrator of the funds of the Santa Hermandad (Holy Brotherhood) and confidant of King Fernando of Aragón), Diego de Deza and Friar Juan Pérez (confessor to Queen Isabella I of Castile). This resulted in the signing of the Capitulaciones de Santa Fe, April 17, 1492.

Capitulaciones de Santa Fe

The Capitulaciones de Santa Fe, documents authorizing and financing Columbus’s voyage, were written by Juan de Coloma, secretary to King Ferdinand of Aragon and signed by Queen Isabella. Through these, Christopher Columbus was given:

- The hereditary title of admiral in all of the lands or seas he might discover, and with the same rank as Admiral of Castile.

- The title of Viceroy (hereditary) and Governor on all of the islands or land that he might discover or conquer in said seas, receiving the right to propose terms for the government in each of them.

- Ten percent of the net product of the merchandise bought, won, found or exchanged within the limits of his admiral territory, setting aside a fifth for the crown.

- Commercial jurisdiction over disputes over trade in his admiralship, as corresponding to the position.

- The right to contribute an eighth to the expedition and participate in the earning in the same proportion.

- The title of “Don”.

Travel Arrangements

There is speculation over the total cost of the journey of the Discovery. It is said that Luis de Santángel, backed by Seville merchants, lent the crown the sum of 1,140,000 maravedies. The admiral contributed 500,000 maravedies, which were supplied by the Italians Berardi, Jacobo di Negro and Luigi Doria. The ships were acquired at a price equivalent to 360,000 maravedies. The Pinzón brothers, especially Martín Alonso, were instrumental to obtaining the participation of the Palos sailors, who doubted the success of the journey. In addition to sailors from Andalucía and Seville, Basque, Italian and Portuguese sailors joined.

They stored enough water and food (flour, crackers, salted fish, bacon and wine) for a six-month period.

The Ships

Three ships were part of the expedition:

- The Niña. Caravel of 52,72 tons was the smallest of the fleet. It had a crew of 20 men, under the command of Vicente Yánez Pinzón.

- The Pinta. Caravel prepared to with stand about 90 tons, had a crew of 25 men under the command of Martín Alonso Pinzón. It was the fastest of the three ships.

- The Santa María. Nao (ship in old Spanish), a merchant ship with three masts, was captained by Christopher Columbus and his crew was 39 men.

The Discovery

The First Voyage

August 3, 1492, the ships embarked from the Puerto de Palos de la Frontera, in Huelva. Nine days later, they stopped in the Canary Islands, where they repaired the rudder of the Pinta and modified the sails of the Niña. The great adventure did not actually begin until September 9.

August 3, 1492, the ships embarked from the Puerto de Palos de la Frontera, in Huelva. Nine days later, they stopped in the Canary Islands, where they repaired the rudder of the Pinta and modified the sails of the Niña. The great adventure did not actually begin until September 9.

On October 12, 1492, land was first sighted, upon arriving at the island of Guanahaní.

Discovered Territories

- Guanahaní, island in the Bahamas archipelago, whose currentname is Watling. It was named the island of San Salvador.

- Rum Cay, belonging to the Bahamas, named SantaMaríade la Concepción on October 14.

- Long Cay, belonging to the Bahamas, was named La Fernandina.

- Crooked Cay, another island in the Bahamas archipelago,was baptized withthe name La Isabela.

- Cuba, namedJuana, October 28.

- Haiti orBabeque(today the island of Santo Domingo, shared by the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Haiti). Columbus named it La Española or La Hispaniola, which means “Little Spain”, December 5, 1492.

Conquest and Colonization

The First Spanish Settlement in the New World. Because La Santa María had run aground on the coasts of Haiti, it was impossible for the entire crew to return to Spain with the ship that remained, as La Pinta and its captain, Martín Alonso Pinzón, had separated from the group a month earlier to search for the island the natives called Babeque. The admiral decided to leave a small group of men in a military fort constructed with the remains of the destroyed ship. This installation was located in what is today known as Punta Picolet in the far northeast of the island. It was named “La Navidad” or “Christmas”, after the day on which the shipwreck occurred, December 25. Diego de Arana, Pedro Gutiérrez and Rodrigo Escobedo stayed in command of the fort and its 39 men. The Europeans also had the support of Chief Guacanagarix, who had been very friendly toward the foreigners since their landing.

First Sign of Resistance. Bordering the island to the east after encountering Martín Alonso Pinzón and Columbus, the ships La Pinta and La Niña arrived together in the Bahía de Samaná, where they saw natives aiming with bows and arrows for the first time. Thus, they named the area “Gulf of Arrows”. The inhabitants of the area were Ciguayo and Macori.

First Armed Conflict. Chief Canoabo and his people destroyed the fort “La Navidad” and killed all of the men in reprisal for the abuses that some committed against the natives and their women. According to the story of Chief Guacanagarix to Columbus when he disembarked in Hispaniola on his second voyage, members of the fort crew had pulled some Tainos from their homes and abused their spouses.

First Spanish Town in America. First Mass. Upon arriving to Hispaniola in his second voyage, and in spite of the destruction of the fort, Columbus decided to build a small Spanish-style villa on the island. The villa was named La Isabela and was located at the mouth of the Bajabonico River. It was quickly constructed and January 6, 1494, Father Boil held the first mass on the continent.

Trading Post Regime. It was the first economic plan implanted by the Spanish. Based on the Portuguese experience on the western coast of Africa, it consisted of the exploitation of unsalaried work by Spaniards, the subjugation of the native peoples, their sale as slaves in Spain and the payment of tribute in gold powder or cotton. The exploitation of natural resources and the indigenous work force could only carried out for the profit of the Crown or Columbus, not for individuals. This situation only caused ill will among the Spaniards, who soon rebelled. In addition, the majority of Tainos could not endure the voyage to Spain, dying of sadness in transit or arriving to the metropolis in critical condition.

Roldán Rebellion. Uncomfortable with the trading post system as Columbus and his brothers governed it, and due to the precariousness of life in Hispaniola and the difficulty of returning to Spain, various groups of Spaniards attempted to rise up in arms against the administration of the incipient colony. The first attempt at insurrection in 1494, led by Bernal Díaz de Pisa, was put down by Columbus. But the second was successful.

Francisco Roldán, Mayor of La Isabela and long-time servant of the Admiral, started the rebellion, winning growing support from the colonists, as he defended the right to search for gold for personal profit, to use indigenous labor, and to take native women as wives as well as the freedom to return to Spain. He also demanded the abolition of the tribute required of the natives.

In 1498, all of the Spanish towns and forts located in Hispaniola, except the towns of La Vega and La Isabela, had joined Roldán. Christopher Columbus had no choice but to concede, signing the Capitulaciones de Azua in 1499. This document named Francisco Roldán as Mayor of the city of Santo Domingo (already founded) for perpetuity, gave amnesty to all the rebels, allowed them the right to return to Spain, to wed Taino women and to use the native work force in search of gold for personal profit. He also conceded the payment of their back salaries, though they had not worked in the past two years, and gave them lands for their Taino slaves to work. This was the origin of the encomienda system.

The Destitution of Christopher Columbus. The way Columbus dealt with the Roldán uprising displeased the Spanish Crown, as the people that occupied the lowest social strata in Spain came to command the colonizing enterprise and acquired a higher economic position, allowing for a possible social ascent. They decided to strip Christopher Columbus of his position as governor of the island and send Francisco Bobadilla to succeed him, who arrived in August 1500. He immediately ordered the imprisonment of Columbus and his brothers, sending them back to Spain in shackles.

Encomienda System. Bobadilla could not defeat Roldán; on the contrary, he had to almost completely accept the Capitulaciones de Azua, and reduced from a third to an eleventh the taxes that the Spanish were required to pay to the Crown for the right to search for gold for personal profit. The next governor, Nicolás de Ovando, arrived in 1502 to subdue the Roldán supporters and sent Roldan and his closest conspirators back to Spain (they died in a shipwreck upon leaving the island). Still, he had to support the distribution of land and Tainos, and favored his men when distributing possessions. The encomienda system was formally established by a Royal Provision issued on December 20, 1503, which eventually became the foundation of the economic structure of conquered Hispaniola and America in the first decades of the colonization. In this mechanism, land and natives were assigned for life to the Spanish colonists, who forced them to work intensively in the mines for the extraction of gold and in agricultural labor, instead of evangelizing them and “ensuring their well-being”.

At first considered by the Crown to be “free vassals” required to pay tribute to the Kings (1501), the indigenous people lived completely enslaves, under the guise of evangelization and civilization, to support Spain’s imperial need to find gold.

Reduction of the Taino Population. The brutal treatment of the indigenous people (considered as property; as a fair compensation for working in the conquista) caused a decrease in their health and life expectancy, which reached alarming levels in the case of Hispaniola, as its population rapidly decreased. The Tainos began to commit suicide en masse and to have abortions, as these methods constituted the only escape from exploitation. From 400,000 that lived on the island at the time of the 1492 arrival of Columbus, by 1508, there were only 60,000.

To this situation also contributed the enraged violence that Friar Nicolás de Ovando unleashed against the indigenous communities that resisted slavery. He beheaded, burned and hung entire towns, no matter the age or gender of the victims. It was slavery or death. In the Jaragua killings, he attacked through trickery, after being received and attended as a distinguished visitor by Chief Anacaona.

The decrease in the native work force obliged the colonists to import indigenous from the Lucaya islands.

The Advent Sermon. Facing the brutality of the treatment of the indigenous people, a voice of protest emerged from the Dominican friars, led by Pedro de Córdoba, Bernardo de Santo Domingo and Antonio de Montesinos. In an event without historical precedent, these priests of the conquering empire voiced their alarm for the suffering inflicted on the conquered. This protest generated a debate on the right to conquer, just or unjust war and the condition of man that resounded on a global scale and came to be one of the foundations for what we know today as public international law and human rights.

In Santo Domingo, the fourth Sunday of Advent, Friar Antonio de Montesinos delivered the following words from the pulpit (“Ego vox clamanti in deserto”):

“In order to make your sins known to you I have mounted this pulpit, I who am the voice of Christ crying in the wilderness of this island; and therefore it behooves you to listen to me, not with indifference but with all your heart and senses; for this voice will be the strangest, the harshest and hardest, the most terrifying that you ever heard or expected to hear…. This voice declares that you are in mortal sin, and live and die therein by reason of the cruelty and tyranny that you practice on these innocent people. Tell me by what right or justice do you hold these Indians in such cruel and horrible slavery? By what right do you wage such detestable wars on these people who lived mildly and peacefully in their own lands, where you have consumed infinite numbers of them with unheard of murders and desolations? Why do you so greatly oppress and fatigue them, not giving them enough to eat or caring for them when they fall ill from excessive labors, so that they die or rather are slain by you, so that you may extract and acquire gold every day? And what care do you take that they receive religious instruction and come to know their God and creator, or that they be baptized, hear mass, or observe holidays and Sundays? Are they not men? Do they not have rational souls? Are you not bound to love them as you love yourselves? How can you lie in such profound and lethargic slumber? Be sure that in your present state you can no more be saved than the Moors or Turks who do not have and do not want the faith of Jesus Christ.”

The Burgos Laws. The campaign in defense of the indigenous people engendered a series of discussions organized by the Spanish Crown in the cities of Burgos and Valladolid. In these sessions, attended by scholars and theologians, the analysis revolved around the human condition of the Indian: whether he was an inferior being that lacked a soul and therefore deserved the treatment given him by his master; or he had a soul, which demanded treatment that facilitated his freedom and evangelization. After almost a year of debates, in December 1512, the Burgos laws were approved, which recognized the “rational” character of the native peoples and stated the following:

- Right to proper nutrition

- Right to access hammocks to sleep.

- Work leave for pregnant women

- Exoneration from heavy loads for men.

- Prohibition of jailing.

- Prohibition of physical punishment.

- Free baptism.

- Obligatory Christian teaching.

- Obligatory construction of their bohíos next to houses of Spaniards.

- Prohibition of bigamy.

- Encomienda limit of 40 to 150 Indians per master.

In addition, the position of Indian distributor was created, directly responsible to the Crown, in order to solve the conflicts caused by the distributions made by the governor of Hispaniola, Diego Colón.

These laws composed the first code of law for the Spanish in the Indies. They were first applied in Hispaniola and later extended to Puerto Rico and Jamaica. But the rights and guarantees conceded to the natives were never implemented and their extermination continued at full speed. Around 1514, in the first Spanish colony in America, only 25,500 Tainos remained; in 1517, the figure fell to 11,000; and between December 1518 and January 1519, a smallpox epidemic reduced it to 3,000.

The Sugar Industry

Decrease in the Spanish Population. From the end of the first decade of the 16th century, the scarcity and concentration of the indigenous work force in the few families of the colonial aristocracy continued to push the bulk of Spaniards to immigrate to other territories that offered greater possibilities for wealth. This situation intensified due to the new discoveries and conquests in continental America. It is calculated that in 1516, the total number of colonists on the island was less than 4,000. In 1528, the greater part of the population was concentrated in Santo Domingo and five towns had disappeared. Not even the growth in sugar production could slow down the emigration.

Decline of Gold. So great was the greed of the conquistadores and colonists that launched the gold extraction in Hispaniola that already in 1515, its quantity was significantly diminished. The decrease of the work force also contributed to the decline in gold activity. In 1519, the mines of the colonists hardly produced 2,000 gold pesos. In order to maintain colonial life on the island, it was decided to structure the economy on another product to export: sugar.

The First Mills. Though sugar cane was brought from the Canaries on the second voyage of Christopher Columbus (1493), it was not until 1503, under the Nicolás de Ovando government, that a resident of La Vega named Pedro de Atienzo produced homemade molasses. In 1506, another resident of La Vega named Aguilón, began to process sugar. Miguel de Ballester, mayor of the town, constructed a small mill for sugar processing in 1514.

The sugar production for exportation only began around 1510, when Gonzalo de Vellosa, motivated by the rise in the price of the product on the European market, constructed a refinery (powered by hydraulic energy) in the south of the island.

The definitive change in the productive orientation of the island came about in 1516, with the government of an order of priests known as the “Padres Jerónimos”, who promoted the sugar industry by distributing lands, loans, and technical, operative and legal services.

The Rise of Sugar. The high sale value of the new activity attracted the members of the governing and bureaucratic class of the colony. These new residents established refineries: Miguel de Pasamonte (treasurer), Juan de Ampiés (clerk), Diego Caballero (secretary to the High Court), Antonio Serrano, Francisco Prado and Alonso Dávila (trustees), Francisco Tapia (mayor of the Fort of Santo Domingo), Francisco Tostado (scribe of the High Court), Cristóbal de Tapia (inspector), and Diego Colón (governor and viceroy of the colony). The men that had enjoyed the large encomiendas during the gold period also benefited.

In 1527, 19 refineries and six mills in the colony functioned at full capacity, the majority on the banks of the Ozama, Haina, Nizao, Nigua, Ocoa, Vía and Yaque del Sur rivers. Sugar production maintained a growing rhythm during the first 60 years: in 1520 it reached an annual quantity of approximately 10,000 arrobas, and in 1580 it reached nearly 90,000 arrobas.

The Slave Trade. The new work force. In the Antillean context, it is impossible to speak of the sugar industry without referring to the black slave work force. The heavy labor of the sugar refineries required muscle force greater than the performance of the indigenous people, in addition to the fact that their numbers had dropped to the extreme. In 1518, by express authorization of King Charles I, licenses or asientos to bring blacks to America (and to Hispaniola) were distributed. These Africans, unlike the indigenous, were employed in intense production labor. Latin Africans, that is, those westernized in Europe and integrated into the entourage of servants of Spanish nobles, had barely stepped foot on American soil before 1501.

To diminish the possibilities of uprising, the refinery owners preferred to import African slaves of different ethnicities. The predominant groups were Zape, Mandinga, Congo, Mondongo, Biáfara, Carabalí and those of the Gelofe language.

On average, 15 to 20 year olds were recruited, though at times they were as young as nine. Their forced work duties occupied up to 18 straight hours per day and included Sundays and holidays. Many died of fatigue and lack of sleep. Others fled to the mountains or defended themselves with weapons.

Slave Uprising. Only four years after the beginning of African slave importation, in 1522, the first African slave uprising in America happened (the rebels belonged to the Gelofe tribe). It occurred in the refineries of Diego Colón and Melchor de Castro and caused the death of 12 Spaniards. It was promptly repressed, but this did not diminish other slave escapes, individually or in groups. According to the situation, they received the following names:

- Cimarrones. Those that fled individually and established them selves in the mountains in order to attack productive units and isolated colonists. These attacks were called “cimarronadas”.

- Apalencados. Fugitives that concentrated in a significant number in a determined location in order to rise up in arms.

- Manieles. Communities of blacks established in the mountains without aggressive ends. They only wanted to live peacefully at the margins of the slave oppression. They created their own laws and cultural habits.

Their preferred places to live protected were San Nicolás, in the Cordillera Septentrional; Ocoa and Rancho Arriba, in the Cordillera Central; Punta de Samaná; Cabo de Higüey and Sierra de Bahoruco.

Black leaders. Among the most famous African leaders that commanded the slave revolts and escapes were:

- Juan Vaquero. He recruited a group in 1537. They roamed the sierras of the south and attacked colonists in village areas.

- Diego de Guzmán. “Cimarrón” of San Juan de la Maguana that attacked said region

- Diego del Campo. He remained in the surrounding areas of La Vega for around 10 years. He was finally turned over the Spanish and came to work toward the persecution of his former companions.

- Lemba. He fought for 15 years in Higüey with 150 followers. He was trapped and executed in 1548.

Increase and Decrease in the Black Population. In the 1540s, the number of African slaves ranged from 60 to 500 per refinery and/or mill, though there were some (the refinery of Melchor de Torres) whose slave workers numbered in the nine hundreds. It is estimated that there were around 12,000 black slaves living in the island with a Spanish population that did not reach 5,000. Due to the incorporation of African women to promote reproduction and of the continuous legal and illegal importation of slaves, the total number of Africans working in refineries, plantations and domestic service ascended to 20,000 in 1568. This number was significantly reduced due to epidemics that plagued the island after the invasion of Francis Drake in 1586. In October 1606, there were 9,648 slaves.

Contraband and Pirates

The Casa de Contratación (Hiring House) of Seville. In 1503, the Casa de Contratación, established by the Spanish Crown to control mercantile activities between Spain and the Indies and to place all colonial production under its monopoly, began its functions. Officials could be found in every port of the conquered lands, charged with supervising production, charging taxes, carrying the accounting books to the Royal House and allocating permission for sailing and trading. The merchandise had to be exported and imported exclusively to and from Seville (exceptionally from Sanlúcar and Cádiz); the monopoly policy banned trade with foreigners. Given that many products were not produced in Spain, and yet had to be imported to Spain before arriving to the Indies, their sale value in Hispaniola at times reached six times more than their original prices.

European investors that did not want to be excluded from the business searched for a way to insert themselves into the economic life of Seville. Through agents, investment in companies and loans to traders, they came to decisively influence the city’s 1543 traders’ association. The immense quantity of gold, silver and other American products arriving to Seville throughout the 16th century would eventually arrive in the hands of capitalists and foreign firms.

Confrontation of European Powers. The Protestant Reformation, Charles V’s imperial intentions, the economic dependence of Spain on England, France and Holland and the struggle for control over the Atlantic brought these countries to align against Spain in 1550. They took advantage of the economic and industrial difficulty of Spain and attacked her on the weakest front by encouraging illegal trade, contraband and the corsair, on the peninsula as well as in its possessions on the high seas.

Corsairs. The corsairs appeared as early as the 1520s. It is known that in 1522, a ship leaving Santo Domingo for Seville was attacked by a French corsair named Jean Florin, who appropriated its entire sugar shipment. In 1537, another French corsair attacked the towns of Azua and Ocoa, burning refineries and houses and taking all that he could; while in 1540, a boat recently docked in the port of Santo Domingo was assaulted by English corsairs.

The Fleet System. From the 1540s, the corsairs’ pillaging intensified. In response, Spanish authorities decided to wall the colonial cities and organize the ships that operated between Seville and the Indies to sail in properly protected boats in fleets or groups to guard against possible attacks. This fleet system established two annual departure dates from Spain and set precise departure and arrival points: the ports of Seville, Veracruz (Mexico), Havana (Cuba) and Nombre de Díos (isthmus of Panama), which meant that a ship arriving to Hispaniola had to separate from the fleet upon arriving in the Caribbean or Havana and make the dangerous journey to the port of Santo Domingo.

Sir Francis Drake. The intensification of tensions between Spain and England due to the Spanish measures to impede the illegal trade between its colonies and English and Dutch ships, as well as the battle over the control of certain American territories (the mare clausum theory against the effective occupation) moved the English Crown to give financial and political support to the sailor Francis Drake to sack the Spanish Indies (1585).

Drake attacked the port of Vigo, in Spain, and afterward turned toward Hispaniola, to whose coasts he arrived on January 11, 1586. The next day, he took the city of Santo Domingo and there he stayed, housed in the Cathedral for an entire month. Drake and his men dedicated themselves to destroying and taking everything of value that they found: sugar, canafistola (a tree whose pulp is used medicinally), ginger, leather, gold and silver, the artillery of the fort, the bells of the church. They only left the city when they received the sum of 25,000 ducats as compensation.

Contraband. Despite Spain’s efforts, from very early on, it was evident that it would be impossible to monopolize trade for all its American lands. In the case of the island of Santo Domingo, the high costs and scarce variety of products from Spain, its already precarious economic existence and its growing marginalization by the Spanish government in relation to the favored colonies, by virtue of their wealth, caused its inhabitants to actively search for commercial exchange with European foreigners. From then on, contraband constituted one of the pillars of its economy. Portuguese, French, English and Dutch traders maintained commercial contact with Hispaniola throughout the 16th century, despite coercive measures applied by the Crown.

Slaves, soaps, wines, flours, fabrics, perfumes, nails, shoes, medicines, paper, dried fruit, iron, steel, knives, etc., were bought by the neighbors of Hispaniola in exchange for sugar, leather, canafistola, ginger and tobacco. At the end of the 16th century, the Dutch dedicated twenty 200-ton ships annually for exclusive trade with Cuba and Hispaniola.

French Occupation of the Western Side of the Island

The Osorio Evictions. Contraband became so important in Hispaniola that early in the 17th century, the majority of the island’s production was acquired by the French, English or Dutch, and to a smaller extent, by the Portuguese, who docked their ships as far away as possible from the city of Santo Domingo (the seat of the royal government). The preferred areas were the north and the west, with the ports of Puerto Plata, Monte Cristi, Bayajá and La Yaguana. In these towns, illegal trade came to be routine and enjoyed the complicity of the local authorities. The owners of the cattle ranches scattered throughout the island, including those in Santo Domingo, preferred to bring their cattle to these areas and sell their leather to the contraband traders, as they could sell at a higher price.

This economic “independence” that the island’s residents exhibited in the face of the Spanish government was encouraged by the European cultural penetration in the “Banda del Norte”, the contraband region, where Protestant baptisms were held with foreign godparents, and where Lutheran bibles were confiscated.

The Crown then took drastic measures: it decided to depopulate the west and northwest of the island. Named the “devastaciones de Osorio” (Osorio evictions) for the governor that implemented the actions, Antonio de Osorio, they went into effect between 1605 and early 1606. As a result, the towns of the Banda Norte were destroyed.

Immediate Effects of the Osorio Evictions.

- Destruction of some 120 ranches, abandoning more than 100,000 cattle and 14,000 horses that swelled the wild livestock population in the depopulated zone. Of the tame cattle that were raised in the region, only less than 10% (about 8,000 head of cattle) could be transported to the new locations.

- Destruction of the sugar refineries and mills of the place, which accelerated the decline of the sugar industry and, together with the loss of cattle andcanafístola and ginger plantations, increased poverty in the entire colony and diminished the commercial importance of Santo Domingo.

- It allowed for the uprising of many black slaves that settled in the depopulated zones.

- Emigration of many affected residents to Cuba and Puerto Rico.

- Depopulation of more than half the island that left it at the mercy of the very foreigners the Crown wanted to avoid.

The Osorio evictions did not lessen the contraband market.

El Situado (Subsidy). The general poverty caused by the depopulations of 1605 and 1606 that, in the long term, affected the entire colony, depleted the fiscal collections of the colonial administration, to the point that it could not cover bureaucratic expenses nor maintenance of the soldiers in Santo Domingo. From 1608, the Spanish government, among other measures including the reduction of the number of soldiers by half, granted an annual subsidy that came from Mexico and was known as “el situado”. This subsidy continued throughout the rest of the 17th century.

Filibusters and Buccaneers. Appropriation of la Tortuga. In 1629, the English and French displaced from the island of San Cristóbal by the Spanish settled on the Tortuga island, adjacent to Hispaniola. This foreign establishment was thrice destroyed by the military forces of the colony (in 1630, 1635 and 1654) and fell into French hands. This made la Tortuga a center of maritime, military and commercial operations whose objective was to conspire against Spanish control and interests, and more concretely, to take over the depopulated zones of Hispaniola, which they named “Tierra Grande”. In fact, in 1648, two groups had moved to the north coast of the island, where they hunted cattle and cultivated tobacco. They were divided into three classes:

Filibusters. Also called “bandits of the sea”, they were adventurers of various nationalities that dedicated themselves to piracy in Caribbean waters, besieging Spanish or Portuguese ships and their ports and cities in the Caribbean. They arrived at la Tortuga to rest and regroup.

Buccaneers. They dedicated themselves to hunting wild cattle and pigs that populated northwestern Hispaniola by the thousands. They took root there, landing on la Tortuga regularly to sell leather and buy supplies of powder, ammunition and clothing. The name comes from a type of roaster (boucan) in which they smoked the meat that they ate.

Inhabitants. Group of adventurers that opted for pursuing tobacco farming on the northern coast of the island, which they sold on La Tortuga.

Attacks on Hispaniola. Throughout the second half of the 17th century, Hispaniola was besieged by the enemy countries of Spain (France and England) that craved control of the island. Two great battles must be mentioned:

- Invasion of Penn and Venables: April 23, 1655, an English fleet arrived to the waters of Santo Domingo, commanded by Admiral William Penn and General Robert Venables and composed of 34 war ships, 7,000 sailors and 6,000 soldiers. In spite of its strength, the fleet was successfully turned back by the Spanish men and military, who, thanks to an intelligent strategy, not only prevented the capture of Santo Domingo, but also forced them to flee in retreat and caused them 1500 casualties. This same fleet immediately invaded the island of Jamaica in the name of England, which was less populated and poorly defended by the Spanish.

- The French Move In land. Definitively established on La Tortuga from 1656, the French intensified the campaign to move inland, position them selves in the depopulated west of Hispaniola and eventually tookover the entire island. In 1668, they established a settlement in the surroundings of the old Spanish city of Yaguana (in the far west of the island) and created a new town named Leoganne. In 1681, a census counted 7,848 people that, under orders from the French government, inhabited the western part of the island.

Tacit Recognition. The Peace of Nimega, signed in Europe in 1678, forced the governors of the Spanish and French towns to come together and establish an active trade of horses, salted meat and cowhide between both groups of settlers (1680). Even if this did not impede bellicose confrontations between them (1690 and 1691, 1694), or refrain Spain from demanding the departure of the French from the island, it did imply that, for the first time, a definition of occupied space was proposed. In an informal and completely circumstantial way, it was proposed that the Rebouc or Guayubín river be established as a border to the north, while in the south, an imaginary line would be traced from said river to the island Beata.

The tacit recognition of a French colony’s existence on the western margins of the island was confirmed by the Peace Treaty of Ryswick, signed by France, the United Provinces, England, Spain and Germany in 1697. Though its content did not refer to those countries’ colonies in America, it did serve to encourage relatively peaceful coexistence, without problems as to the establishment of borders. This situation was reinforced when the grandson of Louis XIV, Felipe Anjou (with the name of Philip V) ascended the Spanish throne and thus allied Spain and France.

Treaty of Aranjuez. June 3, 1777, after decades of negotiations and hostilities between the colonies as to their borders, the Treaty of Aranjuez was signed, which definitively set the northern border at the Río Masacre and the southern border at the Río Pedernales.

Saint Domingue. Since the Treaty of Nimega of 1678, the western part of the island became known as Saint Domingue. Its formal organization, however, began in the early 18th century, when its territory was divided into the Northern, Southern and Western departments, each ruled by a governor and a general manager named by the King of France. On these lands, the French developed an intensive system of plantations that allowed them to produce coffee, cocoa, cotton, indigo and sugar on a large scale. Quickly, Saint Domingue became the richest French colony in the world.

The support of this prosperous economy was the African slave work force, recruited from, among other ethnic groups, the Congo, Arada, Mondongo, Nago, Ibo, Caplaous and Fang. They were subjected to a cruel work regimen that shortened active life by an average of seven years. At the moment of their separation from France, the enslaving colonial bourgeois and white owners composed 6% of the population of Saint Domingue, free mulattos constituted 7% and the black slaves composed 87% (around 610,200).

The slaves’ custom of living together in collective barracks allowed for the mixing of their different languages and French, leading to the emergence of a dialect known as creole.

Treaty of Basel. The radical republican Jacobins that took power in France declared war on Spain (together with Holland and England), which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Basel on July 22, 1795. Through this agreement, Spain recovered possessions lost on the peninsula (Cataluña and the Basque provinces) in exchange for the cession of the colony of Santo Domingo. The state of instability of Saint Domingue since the beginning of the slave rebellion in August 1791 delayed the occupation of the eastern part of the island by France.

Brief Unification of the Island. Protected by the Treaty of Basel, Toussaint L’Ouverture, the black leader of the Saint Domingue revolution, took possession of Santo Domingo on January 26, 1801, unifying the island. One of his first measures in the Spanish colony was the abolition of slavery. He also planned to reorient its productive economy, based on cattle ranching, toward intensive agriculture for exportation purposes. This period of unification was, however, brief, as Napoleon Bonaparte sent an enormous expedition to fight the black revolutionary.

French Occupation. In February 1802, French troops arrived, commanded by General Charles Leclerc. More than 10,000 soldiers arrived to put down the revolution of Saint Domingue and recovered control of the entire island. They could not stop the liberation movement of the old French colony, which, two years later (January 1, 1804), would proclaim the independence of the Republic of Haiti at the hands of the fighters Jean Jacques Dessalines, Alexandre Petion, and Henri Christophe.

Instead, thanks to the group of Spanish Dominicans, the French armada was able to establish its authority in the colony of Santo Domingo, expelling the forces of Paul L’Ouverture (Toussaint’s brother) and later repelling violent Haitian invasions by Dessalines and Henri Christophe in 1805.

The support the Spanish Dominicans of Santo Domingo gave to the French was vital. Many of them rejected the measures taken by Toussaint, as he regulated property and land use, forced them to work in agricultural labor, to which they were unaccustomed, and deprived them of the use of slave labor. In addition, the majority of the population, in contrast to the inhabitants of the ex-French colony, was not considered black, but was composed of white Spaniards and mulattos.

From then on New World-born military man, don Juan Barón, directed military operations to expel Paul L’Ouverture from Santo Domingo and to facilitate the entrance of the French soldiers commanded by General Kerversau.

Emigrations. After the signing of the Treaty of Basel in 1795, many families left Santo Domingo. The signing of the Treaty, the invasion of Toussaint and the wars against the Haitian forces compelled a large number of the residents fled to Puerto Rico, Cuba and Venezuela. The American-born population, accustomed to living in permanent contact with the French on the western side, with their tendency to inch the border further and further east, rejected the idea that without any recognition of their social, historical and cultural composition, they were to be subjected to French authority and joined with the western settlers of the island. They only supported the Napoleonic forces when they realized that the French armies would liberate them from the Saint Domingue revolutionaries and would reestablish slavery, which is what occurred.

The Reconquest and España Boba (Foolish Spain)

The French government of Santo Domingo, led by General Louis Ferrand, favored agricultural and logging activities over the sector that had occupied a principal place in the economic life of the Spanish colony over more than two centuries: cattle-raising. The unpopularity of this policy grew when all commercial trade with the western part of the island (now Haiti) was prohibited, trade that had been in place for centuries and hadn’t been stopped not even by numerous conflicts and invasions.

When Napoleon invaded Spain and took Ferdinand VII prisoner to force him to abdicate the Spanish throne, the American population, affected by the policies applied by the occupiers and offended by the embarrassment to the “Mother Country”, began an uprising that would end the French government.

The War of Re-conquest. The opposition to the French occupation was composed of two main groups with different interests and ends:

- The traders of the south, commanded by Ciriaco Ramírez (assisted by Cristóbal Húber and Salvador Félix), who supported the fight for the abolition of slavery and the proclamation of national independence.

- The cattlemen of the east, commanded by Juan Sánchez Ramírez, one of the emigrants motivated by the signing of the Treaty of Basil that planned a return to Spanish jurisdiction.

The group of cattlemen, richer, more powerful and with more social support, managed to gain power.

The battle of Palo Hincado (November 7, 1808), as well as the Santo Domingo blockade that the army of Juan Sánchez Ramírez maintained for eight months, was essential to the American-born victory.

External support. The colonial government of Puerto Rico, the Republic of Haiti and England supplied men, guns, ammunition and ships to the local forces in their fight against the French. The English support was decisive, though the British Crown charged quite an amount for its participation in the war: immense quantities of mahogany, all of the bells of the churches, part of the best artillery of the cities and the promise that the new colonial authorities would allow the free entry of British ships to ports and would grant their products the same customs treatment as Spanish products.

Upon the end of the War of Re-conquest, the colony of Santo Domingo was left devastated and in absolute misery. The situation continued in the coming years, as the Government of Spain had to confront the internal struggles in its Courts (infiltrated by French interests), the emancipation movements that emerged from the large colonies in South America and Mexico, as well as the threat of the United States to its colonial possessions in North America.

Widespread Misery. There was no substantial change in the economic life of the eastern part of the island during the five administrations or colonial governments between 1809 and 1821:

- For the most part only subsistence agriculture.

- Exports were limited to tobacco, some leather and, later, some honey and aguardiente.

- The production of coffee and cocoa was reduced to a minimum.

- Cattle raising was ruined.

- Scarcity of circulating money.

The colony had to ask again for the “situado” subsidy that, in those years, only arrived on two occasions and for minimal amounts.

Below, an excerpt of the Compendio de la Historia de Santo Domingo (Pags. 25 and 26 of Volume II, 1982.) of José Gabriel García, that summarizes life at this time:

“…it was for this reason that the period came to be known by the common name “España boba” (foolish Spain), the requirements for social life were so few due to the reigning misery that there was no poor class, as all classes had the same needs. Women no longer wore ostentatious dresses and fashion did not change; there were no theaters, nor public parks, nor inns, nor public centers for recreation or prostitution where money could be wasted; such that a small hacienda cultivated by eight or ten slaves produced enough for a family to be considered content, as it produced the same result as any paltry salary indicated by the government budget for the employees of the king, to whom the scarcity of luxury items and the cheap prices of daily consumer goods offered considerable savings. Artisans and farmers satisfied their needs at a low cost, and through the simplicity of their customs, even the unhappiest Dominicans lived tranquilly, given over to their favorite pleasures: food, cockfighting, national dances, bull running and religious festivities, a situation that in no way satisfied the aspirations of the intellectuals, nor did it offer a bright future.”

The Ephemeral Independence

Widespread poverty, the lack of attention from Spain, the social discrimination of the white minority toward the bulk of the population, as well as influences from the French and Haitian revolutions and the American emancipation movements produced a general environment of anti-Spanish sentiment. There were various conspiracies in the period from 1810 to 1821:

- Independence conspiracy of Manuel del Monte (middle class).

- Independence conspiracy of “the Italians”. The leader of the war of re-conquest, Ciriaco Ramírez was part of it (middle class).

- Conspiracy of the cattleman Don Fermín García (middle class).

- Abolitionist and independence movement of Mendoza and Mojarra (slaves and freed slaves)

- Pro-Haitian border separatist movement; it was astutely encouraged by the Haitian president Jean Pierre Boyer (cattlemen, traders, military men, mulattos and slaves from the border area).

The Independent State of Spanish Haiti. There was another group of conspirators, composed of high officials in the government and the army that deposed the Spanish administration to proclaim an independent state that would ally itself in confederation with the Bolivarian project in Gran Colombia. The head of the movement was José Núñez de Cáceres, who had served as lieutenant of the governor and general advisor, and that in 1821 obtained the position of judge-advocate and prresident of the Universidad Santo Tomás de Aquino. It was Núñez de Cáceres who proclaimed the “Independent State of Spanish Haiti” on December 1, 1821.

The Haitian Invasion. The independence proclaimed by José Núñez de Cáceres lasted only a short time. The Haitian president Jean Pierre Boyer, who had been trying to build upon support of the Dominicans on the border for unification with Haiti, invaded the eastern side of the island and took possession on February 9, 1822. He arrived with an imposing army of 12,000 men, knowing that Núñez de Cáceres did not have the support of the white owners, which were pro-Spanish, nor the support of the discontented slave and mulatto population since the new Constitution did not establish abolition of slavery. Boyer, in addition, had acquired the tacit approval of the tobacco producers and businessmen of Cibao.

The Haitian Domination

Key measures of the Boyer government.

Social and Legal Measures:

- Proclamation of political and social equality, that is, the elimination of slavery.

- Modification of the property and land tenant system. The eastern side of the island passed from Spanish control, based on communal lands and multiple and irregular possession of land, to the French regime (which was also applied in Haiti), characterized by absolute private ownership of land guaranteed by titles issued by the State.

- Incorporation of Dominican residents into the Congress of Haiti.

- The creation of a Council of Notables for municipal administration.

- Establishment of marriage as a civil act.

- Classification of children as legitimate and natural (according to whether they were born in or outside of marriage).

- Prohibition of gambling and cock fights. The latter were only allowed in the country side on Saturday or Sunday.

- Institution of obligatory, secular and free education.

- Recruitment in the army of all men from 16 to 25 years old. This caused a loss of students for the Universidad Santo Tomás de Aquino and, therefore, it had to close its doors.

- Prohibition of the use of the Spanish language in official documents.

- Limitation of the celebration of traditional religious festivities.

Economic Measures:

- Confiscation and distribution of: a) all lands that did not belong to individuals; b) moveable and immovable propertyand all territories and their respective capital that were property of the Spanish Crown, as well as those that were property of the Catholic Church; c) all moveable and immoveable property of the people that had emigrated before and after the unification.

- Obligation of all new land owners (who had a right to a minimum of76.8 hectares) to dedicate the land to fruit cultivation for exportation and to cropsnecessary for their subsistence.

- Registration of all agricultural workers to the lands: they could not pursue any other activity without previous authorization. Their children were also obligated to pursue agriculture and had to have special permission to go to school. In the beginning, all that were not government officials or had a recognized profession had to pursue agriculture.

- Priority given to coffee, cocoa, sugar cane and indigo crops, which were to be exploited according to the French system of large plantations.

- Prohibition of pig breedingor the establishment of cattle ranches in land areas of more than 380 hectares.

- Suspension of payment of the salaries that priests and members of the ecclesiastical council received from the State.

- Prohibition for Dominicans to engage in trade. Only foreigners, Haitians and representatives of international trade houses could engage in the activity. The Dominican that wanted to pursue trade had to become a Haitian citizen.

Dominican Reaction. The Boyer declarations elicited repudiation from the majority of the population in the eastern part of the island. On one hand, the confiscation and distribution of land seemed limiting due to the communal tenancy of lands without exact limits, as well as the group of rights of possession, division, use, sale and participation that had been in effect since the colonial era made it difficult to determine the actual owners and the rights of each. On the other hand, the attempt to impose agriculture for exportation found opposition among large landowners and small peasants that, for the majority, were accustomed to living from the cattle ranch, on subsistence farming and, to a lesser extent, from logging.

The opposition to the Catholic Church, most affected by the confiscation of lands and goods, and the direct hit to the Archbishop Pedro de Valera, also had repercussions in the majority of the population, which saw in this and other measures (limitation of the celebration of religious festivities, prohibition of cock fighting and gambling, obligatory agricultural labor, no use of Spanish in official acts and documents, closure of the university and military recruitment of all young men) a group of policies that contradicted their nationalist sentiments.

The grievance increased due to the economic measures and fiscal obligations imposed on the eastern half of the island to pay the sum of 150 million francs in compensation for the harm caused by the war for Haitian independence. The fine was demanded by France solely from the inhabitants of the French part of the island of Santo Domingo.